In his 1971 hit, Marvin Gaye laments “make me wanna holler, the way they do my life…” The lyrics to this song can be applied to modern-day events surrounding the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement and the general plight of Black people in the U.S. Embedded in Gaye’s songs and other social justice anthems is that there can be no reconciliation or restoration without the acknowledgement of truth. It is in the spirit of acknowledgement and reconciliation that we, two Black language education professionals, pen this piece.

We focus on language and language education organizations because we have both insider and outsider perspectives of them and of the larger English language teaching profession. We personally know the isolation and marginalization (Curtis and Romney, 2006; Cooper and Bryan, 2019; Toliver et al., 2019) that occurs at some language education conferences and within the profession.

Here, we acknowledge the myriad of ways that language is weaponized and used as a tool to promote White supremacy and racism as we focus on both the said and the unsaid during the current BLM revolution and within selected position statements. We acknowledge that there is much work to be done with regard to eliminating anti-Black racism and decentering Whiteness in these arenas and we are willing to be a part of this work (albeit in ways that do not further burden or traumatize us). We end with considerations for (language) education organizations as they chart paths forward to rise up and support historically marginalized/minoritized members of their organizations.

The Power of (Coded) Language

While the intention of this piece is not to teach a history lesson, as we mentioned before, it is important to acknowledge truths. Language is a most powerful weapon. English, one of the major languages of colonization, was weaponized prior to the first African slaves arriving on the shores of what was claimed and named America. Throughout the history of the U.S., the English language has been wielded like the whips of 18th-century white slave traders, the water hoses and dogs of the Jim Crow era, and the batons, guns, and knees of modern-day police officers.

Crummell (1862) juxtaposed the effects of the English language upon African slaves, as he characterized it as both a language of unusual force and power and the language of freedom. Language is a major part of what makes us human. It is through language that we articulate our most complicated ideas, express our dynamic identities, and uplift our cultures. It is also through language that we demonstrate our ability to be inhumane and apathetic about the plight of Black and Brown peoples. Black peoples have been especially and historically subjected to the physical assaults of White supremacists and the spirit-murdering of White supremacy. White supremacist thought is embedded in the racialized discourses that portray Black and Brown peoples—their languages, cultures, and ways of living—as inherently inferior.

Coded language, language that triggers racial stereotypes and other negative associations without the stigma of explicit racism, is a favored tool of White supremacists and closet racists. They use veiled language to foster anxiety among certain audiences and to dehumanize people and communities of color. Throughout the past three years, and especially during the current Black Lives Matter revolution, coded language has been evident across television news cycles, social media platforms, and political speeches. For example, Black protesters are often referred to as rioters. Even when protests organized by Black and Brown people are peaceful, they are often labeled as riots. The term riot evokes feelings of fear and an anticipation of destruction. Similarly, there is hardly an instance when a group of White men are labeled thugs. Instead of being described as thuggish, they are often described as rowdy and mischievous, even when they are looting, turning over cars, and starting fires. White supremacist ideology has racialized the term thug.

In June 2020, in a statement opposing the removal of Confederate statues, a particular politician stated, “They hate our history, they hate our values… Our country didn’t grow great with them.” Who exactly is “they/them”? We would assume that they/them are all of the Americans who do not share a racial or ethnic identity with Confederate leaders (who were by all means traitors and domestic terrorists). In this context, the terms they/them are racialized and clearly refer to non-White peoples. States’ rights has always been code for slavery. So when supporters of the Confederate flag and those who hail Confederate generals of the Civil War explain that they were pro states’ rights, they either don’t really know what they are talking about and simply are repeating what they have heard or they really are opposed to the abolition of slavery, and if all had gone well, Southern states would have been allowed to keep Black people enslaved.

“All lives matter” has become a counter-discourse to “Black lives matter.” We no longer view this phrase as coded language. Discourse such as this is blatantly dismissive of the racism faced by Black people in the U.S. We know that all lives matter. So, when we say that Black lives matter, we do not mean that only Black lives matter, or that they matter more than other lives. We are highlighting the need to protect the lives that are in danger.

All lives can’t matter until Black lives matter. Likewise, when scholars of Black languages holler “Black languages matter,” we are highlighting the race-based linguicism and marginalization faced by speakers of Black languages in the U.S. context (Baker-Bell, 2020; Cooper and Bryan, 2020).

Make Me Wanna Holler: Position Statements on Anti-Black Racism

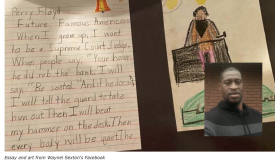

Unlike in BLM movements of the past, the murder of George Floyd is a call to action for (language) education professionals. Education professionals cannot be silent on social justice issues. Floyd’s second-grade teacher, Waynel Sexton, wrote in a Facebook post, “I taught George Perry Floyd in second grade. He was a quiet student and a good boy. He wrote of becoming a Supreme Court judge. How could his dream have turned into the nightmare of being murdered by a police officer? It just breaks my heart” (Magee, 2020). Every Black male whom language education teachers come into contact with in their classrooms could be a George Floyd, with both his aspirations and dreams and his fate of being killed at the hands of those charged with protecting and serving. This makes us wanna holler! Individuals and organizations must call out coded language and discourses that covertly racialize terms, marginalize people, and silence history, even when they come from the very institutions by which we are employed or in which we claim membership.

English language education and literacy organizations have inherently embraced Crummell’s second concept of English as the “language of freedom” (p. 13). The utility and value of English literacy is at the core of these organizations’ missions, so it should be natural for us to operate in a way that is truthful, honest, and supportive of members who have been oppressed by racial and linguistic violence. For example, the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) is dedicated to “improving the teaching and learning of English and the language arts at all levels of education.” In addition, NCTE describes its mission as “to promote the development of literacy, the use of language to construct personal and public worlds, and to achieve full participation in society, through the learning and teaching of English and the related arts and sciences of language” (NCTE, 2020). In its position statement1 regarding the killing of George Floyd and the BLM revolution, NCTE refers to its past and present work, urges everyone to vote in November to resolve the problem, and studiously avoids the use of the word Black. Nevertheless, it credibly offers links to explicitly anti-racist work it has produced and “member gatherings” it holds. Although it provides concrete actions, its position statement is more about the organization’s beliefs than specific commitments it will make.

The Literacy Research Association (LRA) describes itself as a community of scholars dedicated to promoting research that enriches the knowledge, understanding, and development of lifespan literacies in a multicultural and multilingual world. LRA is committed to ethical research that is rigorous, methodologically diverse, and socially responsible. Central to its mission, LRA mentors and supports future generations of literacy scholars. In its position statement,2 LRA did manage to foreground anti-Blackness and anti-Black violence. It names “Black, Indigenous, and Latinx communities” explicitly and directly calls for scholars to focus their energy on the dismantling of racism. It is able to refer to the work of Haddix (2019) and Willis (2019) countering deficit-based narratives, and the statement is much closer to the promises of direct action than those of many other organizations. Nevertheless, Toliver et al. (2019) highlighted the ways in which marginalized voices often go unheard at LRA conferences. One of the members said:

“I dream LRA will one day commit to equity and justice, not to a superficial stance on substantive diversity that exists in name only. I dream that calls for proposals that highlight activism, love, and radical courage are met with membership-wide excitement and joy, not disdain and cynicism. I dream [that] LRA can learn to love the minoritized scholars who inhabit the space and that all members from dominant identity and academic positions will understand that making room for others does not mean they are being pushed out of the organization. LRA, as an international organization, is big enough for all of us” (p. 55).

LRA still has work to do within its membership.

Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) International Association’s mission is to advance the expertise of professionals who teach English to speakers of other languages in multilingual contexts worldwide. It suggests that this is accomplished through professional learning, research, standards, and advocacy. One of its core values is a commitment to equity, diversity, multilingualism, multiculturalism, and individuals’ language rights. Although its statement was one of the first to be released, it leaves a lot to be desired, as it does not go as far as many of the other statements. The position statement3 begins by describing the association’s “sadness, disgust, and anger at the senseless killing of George Floyd,” but the statement does not center anti-Blackness in the discussion, referring only to a “person of color.” In his June 2020 blog, Gerald argues that “our field of English language teaching (ELT), or TESOL, intentionally centers whiteness without naming it, and that this upholds white supremacy in a variety of harmful ways.” He decries TESOL’s statement, aptly asking TESOL members to read the message and count how many times the word Black is used. The sad truth is that Black does not appear once. And the statement can be perceived as the organization praising itself for its supposed progressivism “during uncertain and turbulent times,” lamenting that “equality and justice for all” have yet to be achieved. The buzzwords equity, diversity, multilingualism, and multiculturalism make appearances, followed by an invocation of Dr. King that manages to also implicitly condemn revolutionary action by urging “peaceful protests,” despite King’s actual beliefs and words on the subject.

Finally, the International Literacy Association (ILA) manages to get much closer to the ideal for such a position statement,4 as it proposes the sort of concrete action needed for systemic change and, most importantly, commits to making changes within its own practices. The ILA criticizes the overwhelming Whiteness of academia, pledges to improve the BIPOC submission and publication rate at its journals, and unique among these organizations, discusses funding. It is, however, a bit abstract, as the association promises to “get involved in efforts to fund more literacy research that addresses inequities across racial groups” (emphasis ours), so who knows what will come of it, but any promise that excludes the reality of economic exploitation is likely to fall short. Nevertheless, the ILA’s statement was strong and a better model for language education organizations.

Fight the Power: Making the Performative Actionable

In their 1990 album, Public Enemy sang “Fight the power. We’ve gotta fight the powers that be!” Now is the perfect time for (language) education organizations to fight the power. They must look critically at their policies and practices with regard to social justice issues and inclusivity. As Gerald (2020) states, “We can’t fix a problem we can’t name. And we cannot fight anti-Blackness as long as we center and remain invested in whiteness” (para. 6). We must encourage change at both the structural and individual levels. We use we deliberately, as both of us have been, or are, members of several of these organizations and have thus benefited from their work in some fashion. Nevertheless, we feel it is vital to be critical so that they might prioritize the need to be more inclusive.

Education organizations must go beyond listening sessions, climate surveys, the hiring of diversity officers, and the appointment of committees. As Gerald (2020) proclaims and what organizational servant leaders are now learning is that statements must be a combination of both linguistic specificity about anti-Blackness and an action-based institutional commitment, be it past, present, or future, to dismantling oppressive systems that exist and impact their memberships.

We provide an example of an action-oriented statement from an unlikely source, Raaka,5 a very small Brooklyn-based chocolate company. In the immediate aftermath of the uprising, Raaka sent out a message6 affirming “solidarity with our Black employees, friends, and neighbors.” They acknowledged those in their midst who identify as Black and who were most likely the most wounded by seeing an image of someone who looked like them be killed by the police.

More importantly, they closed their online store for several days and pledged to donate their assumed proceeds to necessary causes, which they then named, an immediate financial step taken. Like Raaka, language education organizations must be able to show the ways in which they contribute financially to making their organizations more inclusive. On an annual basis, how many Black and Brown scholars are supported through organization-based fellowship and mentorship programs? Are there programs that specifically assist with the professional development of Black and Brown language/literacy graduate students and junior scholars? Are Black-identifying groups within the organization encouraged, supported, and viewed as a resource?

Raaka also provided links to Black-owned chocolate companies (that is, their competitors) and urged people needing treats to spend their money there. A few days later, they reopened their store, but they provided screenshots of their donation receipts to Black organizations. Yes! Raaka was willing to provide receipts, literally.

We argue that education organizations, too, must be willing to provide receipts. Are we auditing existing social justice and diversity programs to see if they are truly leveling the playing field? Are we utilizing existing structures where we can offer our services and solicit expertise? For example, Historically Black Colleges and Universities have been training language and literacy teachers from the beginning of their existence. State-funded HBCUs do not get nearly as much funding as their predominantly White counterparts (see a most informative article in Diverse Education),7 so it would be an amazing gesture for language education organizations to reach out, encourage, and support these and other U.S. minority-serving institutions by providing pro bono professional development opportunities; to consult with faculty from minority-serving institutions to assist with webinars; and to seek them out to contribute to research publications and grant-writing opportunities.

In ending its statement, Raaka acknowledges, “We have a lot of work to do to be actively anti-racist as a small company, but we’re listening and learning.” Whereas most of the professional organizations are proud of what they feel they have already done, this company, in our view, has done by far the best work as it pledges to continue learning, as should all who seek to dismantle anti-Blackness, The contrast is clear and sharp, and that these organizations, composed as they are of language scholars, could not find the right words for this crucial moment is deeply disappointing, though, unfortunately, not altogether surprising.

We Will ‘Rise Up’… Hopefully

In conclusion, we can only hope that (language/literacy) education organizations that benefit teachers and students within the U.S. and across the globe will rise up. The overall themes of position statements should probably not begin with claims of inclusivity and/or superior ability to make their Black and Brown members feel welcome. Like with most of the institutional structures in the U.S., there is too much evidence to the contrary. We must take this opportunity, the here and now, to acknowledge the raciolinguistic ideologies (Flores, 2020; Rosa, 2019), linguistic imperialism (Canagarajah, 2002; Phillipson, 2006), and White supremacist thought inherent in English language teaching.

As language professionals who identify as Black, we will continue to do our parts in re-imagining what language organizations can be if only they take this moment to create actionable goals that are specific (related to decentering Whiteness in literacy and language teaching), measurable (monitor diversity/inclusivity goals and keep receipts as Raaka does), attainable (be realistic by utilizing the expertise of your Black and Brown members… and don’t expect this expertise to be provided for free), relevant (stay the course because acknowledging dominant positioning can be hard for those who benefit from it), and time-based (the time for equity and inclusion is now!).

References

Baker-Bell, A. (2020). “Dismantling Anti-Black Linguistic Racism in English Language Arts Classrooms: Toward an anti-racist Black language pedagogy.” Theory into Practice, 59(1), 8–21.

Canagarajah, S. (2008). “The Politics of English Language Teaching.” Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 1, 213–227.

Cooper, A. C., and Bryan, K. C. (2020). “Reading, Writing, and Race: Sharing the Narratives of Black TESOL Professionals.” In Language Teacher Identity in TESOL (pp. 125–142). Routledge.

Crummell, A. (1862). “The English Language in Liberia.” In The Future of Africa. Charles Scribner.

Flores, N. (2020). “From Academic Language to Language Architecture: Challenging raciolinguistic

ideologies in research and practice.” Theory into Practice, 59(1), 22–31.

Gerald, JPB. (2020). “TESOL, White Supremacy, Whiteness, and Anti-Blackness.” Uncharted TESOL Blog, the New School, June 24, 2020. https://blogs.newschool.edu/unchartedtesol/2020/06/24/tesol-white-supremacy-whiteness-and-anti-blackness/

Haddix, M. (2019). Presidential address delivered at the 69th annual conference of the Literacy Research Association. https://youtu.be/2RqC0fNWCU0

Magee, N. (June 5, 2020). “George Floyd’s Second-Grade Essay Reveals He Wanted to Be a Supreme Court Justice.” theGrio. https://thegrio.com/2020/06/05/george-floyd-2nd-grade-letter-supreme-court-justice/

Phillipson, R. (2006). “Language Policy and Linguistic Imperialism.” In An Introduction to Language Policy: Theory and Method (pp. 346–361).

Rosa, J. (2019). Looking Like a Language, Sounding Like a Race. Oxford University Press.

Toliver, S. R., Jones, S. P., Jimenez, L., Player, G., Rumenapp, J. C., and Munoz, J. (2019). “This Meeting at This Tree: Reimagining the town hall session.” Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 68, 45–63. DOI: 10.1177/2381336919869021

Willis, A. I. (2019). “Race, Response to Intervention and Reading Research.” Journal of Literacy Research, 51, 394–419.

Links

- https://ncte.org/blog/2020/06/ncte-takes-stance-racism

- https://www.literacyresearchassociation.org/statement-from-lra-leadership

- https://www.tesol.org/news-landing-page/2020/06/01/tesol-statement-on-racial-injustice-and-inequality

- https://www.literacyworldwide.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/joint-statement-racial-injustice.pdf

- https://www.raakachocolate.com

- https://www.instagram.com/p/CBEZbGOhfXR

- https://diverseeducation.com/article/73463

Kisha C. Bryan is an advocate for language learners and literacy/language teachers who are often marginalized due to their racial, ethnic, and/or linguistic identities. She is an assistant professor of ESL education at Tennessee State University, current co-chair of the Diverse Voices Task Force in the TESOL International Association, and a 2017–2019 Literacy Research Association STAR Fellow.

JPB Gerald is an education doctoral student at CUNY–Hunter College, whose scholarship focuses on language teaching, racism, and Whiteness. You can find his public scholarship at jpbgerald.com and his excessive Twitter opinions @JPBGerald.